The AS-CHEM cluster (like many other high-performance computing clusters) runs on a Linux-based operating system called CentOS so navigating its filesystem requires some knowledge of the Unix shell. As this guide is written for those without much computer experience, the more experienced reader may feel free to skip this section.

What is the shell?

The shell is a program that exposes a computer’s operating system to a user or another program.1 It is not the same as the program with which will interact with it: the terminal; however, since the terminal is the main mode of communication with a shell, you commonly see these terms used interchangeably.

There are many different shells; the most common, and the one we will use here, is the bourne again shell or bash, but others, like zsh, tcsh, and csh, do and can also be used here with slight modifications.

bash is the command-line shell, but it is also the name of the accompanying scripting language. So in this course we use the bash program to send commands to the operating system using the bash language.

Navigating the filesystem

When navigating a computer system via a command-line system you exist in a directory (imagine the little streetview guy wandering around a city, or, if you can remember it, Zork) and, unless otherwise specified, commands take action in and on the directory in which you are currently located a.k.a. the current working directory.

When you open terminal you should see something like:

user@computer | ~ $

This is called the terminal prompt or the command prompt; it displays your username and the computer that you’re logged on to. The ~ is a shorthand for your home directory, but more on that in a bit. Commands are entered after the $.

To view the current working directory type pwd:

NathanLui@local | ~ $ pwd

/Users/NathanLui

Moving around

To navigate between directories use the command cd followed by the path of the directory you want to enter. For example, to navigate to the Documents folder use cd Documents. Notice how the ~ changes to display the path to the new directory ~/Documents.

NathanLui@local | ~ $ pwd

/Users/NathanLui

NathanLui@local | ~ $ cd Documents

NathanLui@local | ~/Documents $ pwd

/Users/NathanLui/Documents

The terminal will understand two types of paths: relative or absolute. A directory’s absolute path begins with / and describes the exact location of the directory. The command pwd returns a directory’s absolute path. A directory’s relative path describes the location of a directory relative to the current working directory.

In the example above the absolute path of Documents is /Users/NathanLui/Documents, but relative to our home directory the relative path is just Documents.

Looking around

Use the command ls to look inside the current working directory.

NathanLui@local | ~/Documents $ ls

launchCodes.txt playGame.sh Presentation Slides

Of course this doesn’t tell us much about these files. So we use the flag -l

NathanLui@local | ~/Documents >>> ls -l

total 9688

-rw-r--r--@ 1 NathanLui 45K Jul 6 15:19 launchCodes.txt

-rwxr-xr-x 1 NathanLui 192B Jun 29 11:25 playGame.sh

drwxr-xr-x 9 NathanLui 627B Jun 1 2021 Presentation Slides

This tells us more (sometimes more than we want to know) about our files and folders. On the far left of the output is the list of file’s permission, or mode of access. These modes control what the file is allowed to do and who is allowed to do them. There are 3 access levels for any file: the owner, the group, and everyone. The 10 characters of the permissions section designate read, write, and execute (run) access for these three groups (plus a general descriptor at the beginning).

For example, the file launchCodes.txt has the access descriptor -rw-r--r-- meaning it is a regular file - for which the user (u) can read and write but not execute rw-, my group (g) can only read r--, and others (o) else can only read r--. Whereas, the file playGame.sh is a program, or a shell script. A shell script is run (executed) by the user, so it needs the permission code x to to function properly. Notice above that playGame.sh can be executed by the user, group, and everyone else. Sometimes you’ll need to change permissions (usually, you need to give a file executable permission) and this can be done using the chmod command (change mode) followed by the new set of permissions. A more detailed explanation of file atributes and permissions can be found here.2

Making and editing files

To make or edit files in terminal you’ll use one of the preinstalled text editors: vi, vim, or nano. My personal favorite is vim. If you don’t have experience using a command line text editor it will take a bit of getting used to. A cheat sheet for vim can be found here.3 nano is the command-line text editor that generally is the easiest to pick up for first-time users. You can find the full documentation4 and cheat sheet5 on its website. If editing files in the terminal isn’t your style, you can always download your file of interest from the cluster and edit it locally and then upload it back when you’re done, but this will get tedious.

To edit or create a file simply type vim /path/to/file. If the file already exists vim will open it and you can edit to your heart’s content (of course, it should go without saying that text editors can only edit text based files). If the system can’t find the file vim will open a blank file with the path/name that you specified. vim will not save that file until you write it with :w.

Asking for help

Help will always be given in Linux to those who ask for it.

—Harry Potter’s IT teacher, probably…

These are the essential, but very basic Unix commands to get you started. There can be quite the learning curve when transitioning from a graphical system to the command line so I’ll leave you with two of the most important commands to remember when you’re stuck: man and apropos.

Say you want to take a peek at the permissions of a certain file, but you can’t remember the flag for the detailed output. The man ls command brings up the manual page for ls. In it you’ll find detailed documentation for the command including its signature, description, options, examples, and related commands. To exit the manual page press q. The Linux manual is also available online.6

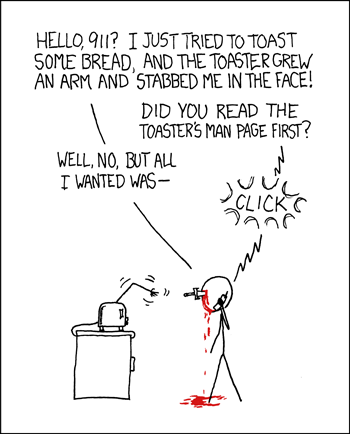

Figure 1. Always read the manual! xkcd 293

Figure 1. Always read the manual! xkcd 293

Now, that’s nice if you know what command you need for, but say you want to make a new directory (folder) and you’re not sure how. This is where apropos comes in.

NathanLui@local | ~ $ apropos make directory

...

makewhatis(8) - create whatis database

makewhatis.local(8) - start makewhatis for local file systems

mkdir(1) - make directories

mkfifo(1) - make fifos

mklocale(1) - make LC_CTYPE locale files

...

Apropos searches the linux manual pages for the query and returns results sorted alphabetically.

Other useful commands

mkdir </path/to/directory> Make a new directory

rmdir </path/to/directory> Remove a directory

rm </path/to/file> Remove a file

mv </path/to/file> </path/to/directory> Move file to new directory

cp </path/to/file> </path/to/directory> Copy file to new directory

cat </path/to/file> Display the contents of a file

bash </path/to/executable> Run the executable

Let’s build a program

Go to the next lesson to write your own script!

Software |

My First Script |

References

(1) Shell (computing)

(2) File permissions

(3) https://www.radford.edu/~mhtay/CPSC120/VIM_Editor_Commands.htm

(4) nano documentation

(5) nano cheat sheet

(6) The Linux Manual

(7) xkcd:rtfm